BACK IN THE DAY WITH MY DAD

By Shaun Tomson

1970 – Buffels Bay, South Africa – I had just become top seed for the South African Surf Team to compete in the World Championship at Bells Beach, Australia.

My dad didn’t like to talk about the shark attack. He wouldn’t directly evade the issue but he’d skirt around its edges with his own brand of strange humor. “The shark died of blood poisoning” or “I don’t know who got the bigger shock, me or the shark.” My mom said he experienced terrible nightmares but us children never saw them. He was always smiling; totally un-self-conscious of the terrible scars the black fin’s teeth had left on his arm. He could find humor in any situation. The attack happened shortly after he had returned from the Second World War in 1946. He had been a tail gunner in American B25 Marauders flying for the SAAF and beating off fighters with his twin 50 caliber Brownings and dropping 1000-pound bombs on the Italians and Germans.

After the attack he’d traveled to San Francisco for extensive surgery to attempt to regain the use of his right arm and had to undergo a series of skin grafts from his stomach. He’d tell us with a smile that the scars on his stomach were from ack-ack, anti-aircraft fire. After the surgery he travelled to Hawaii to recuperate. He stayed in the Royal Hawaiian Hotel and befriended the Kahanamoku clan – Duke had been his hero as a young boy and my Dad fell in love with the Hawaiian culture and lifestyle. We were the only house in South Africa where shoes had to be left outside the front door. His love for Hawaii rubbed off on me and Duke became my hero as well. My barmitzvah present wasn’t a sheaf of stock certificates like my classmates but a trip to Hawaii, to the island that he loved. He found a smile in any situation in life. He gave my sister Tracy a pumpkin for a birthday present. He’d been telling her for weeks that he was going to buy her a pumpkin, and when she opened the beautifully wrapped box, there it was and she burst into tears.

He’d just pulled through from the attack, after being in critical condition for some time. For years afterwards I’d have people come up to me on the beach, “You’re Ernie’s son. I helped pull your father in.” He told me that when he got hit the shark lifted him straight out of the water and dropped him back in, and with blood all around, the fear really set in. He was riding a little wooden surfboard. He said he’d never seen the ocean clear so fast. Men were scrambling up the pilings, shredding themselves on the mussels, so people thought that there were multiple attacks. Only one swimmer, Brian Biljoen, had the courage to pull him in. He was rushed to Addington Hospital on the beachfront and the doctors packed his arm in ice. It was a blazing hot summer so when the hospital ran out of ice, all the hotels on the beach would bring in ice. He’d been one of the country’s best swimmers and lifesavers and was training for the European games and Olympics. The shark bite ended his swimming career. He was 22 years old, a great athlete, and it had all come undone.

Ernie Tomson – South African Junior Swimming Champion – late 1930s.

Amazingly my father never let the shark attack scare him away from the sea – he had a deep love of the ocean and the beach life and he transferred that love to his children. My earliest memories are of the beach, going for a tiger tim. He’d talk in rhyming slang. The beach boys, like the Cockneys had their own language: a swim was a tiger, money was tom,shortened from tom funny. Our beach was a narrow stretch of sand wedged between a ribbon of high-rise hotels and apartments to the west, and the Indian Ocean to the east. The beach had always been a big part of our family life; my earliest memories are of sitting on the sand with my Mom and Dad beside me, with a big hamper of food in front of us and an umbrella overhead. My Dad would sit in his deck chair with a cigarette and I’d impatiently tug at his arm and say “ Dad, let’s go for a tiger, let’s go for a tiger”.

My Dad would take me down to the surf, pointing out the dangers of the jellyfish, the stinging bluebottles with their zinging tails, and the powerful fast moving rip tides that ran out beside the piers, stealthily sucking out swimmers. The dangers of sharks he seldom spoke about even though he’d been hit less than 20 years before. So I knew about the dangers early but they were all brushed aside and we’d plunge in and swim out to the backline looking for a suitable wave to catch, hoping to find a broadie, a wave that would enable us to track across the wall, parallel to the shore. Sometimes we’d just get a foamie, a mass of rolling whitewater and we’d body surf straight in, trying to keep our bodies as stiff as possible and my Dad would raise one leg while he raced forward, like a rudder in the wind; I don’t know what it did and I still don’t but it sure looked good, so I copied that cool style of his. From body surfing it was a quick progression to surfoplanes, a corrugated rubber pillow about a meter long with handles on the front. My brother Paul, cousin Mike and I would battle our way out to the backline and bomb down the dumpers, screaming with the adrenalin rush of the drop. And then my Dad got me my first board, a 4’6” Wetteland Surf Rider, a mass-produced mini-board, with red rails and a clear chop mat center. To me I had a never seen anything as beautiful before, my very own, brand- new little surfboard.

I can remember that first wave on a board like it was yesterday. It was 1965 at the Bay of Plenty and I was 9 years old. I waxed up with a candle and made my way out through the shorie, the impact zone where the waves broke right on the sand. With the world to my back and the horizon ahead I was truly on my own. The foam rumbled towards me, I swung my board around, dug my little arms hard into the water and paddled. The whitewater picked me up, shot me forward and I leapt to my feet and stood up. That feeling of stoke instantly imprinted itself on my being; happiness and fear, exhilaration, speed, conquest all melded together into one rush of sensation. And the view, that overview of land, looking over and above it all, racing along on an invisible band of energy, three inches above the water, separated by just a little sliver of glass fiber and for a brief moment, a master of my little universe. Surfing right there, right then, gripped me hard and fast and just never let go.

My Dad could see how much I loved surfing and it became his interest as well. He couldn’t surf because the shark attack had severely limited the use of his right arm but his enthusiasm for the new sport I loved knew no bounds. My Dad was already sports mad – rugby was his favorite and he had his season tickets at the half way line at Kings Park so every Saturday afternoon it was off to the rugger to watch his teams, Collegians or Natal, to see the legendary fly half Keith Oxlee try to get his ball down the line to the winger Trix Truter. Natal wasn’t the powerhouse of the ‘80’s but my Dad loved the action – it wasn’t about whether you won or lost, or how many tries you scored but how you played the game. Hit him low and hit him hard was his credo and he loved courageous crashing tackles. To my father sport was a game of honor – there were no gray areas – He would tell me there is nothing more despicable than someone who cheats at sport. You win or you lose and when you lose, you lose like a man and when you win, be humble about it – all powerful lessons for his teenage son.

Along with his brother Sonny, my Dad owned Durban’s largest panel beating business so of course he made and designed the town’s first beach buggy for our trips to the beach – blue sheet metal covering a VW bug chassis with a blue and white striped roof and a little white fringe and stacked up roof racks where we would permanently leave our boards. When the surf was up and the southwest was blowing he would pick my brother and I up from school, stop by my cousin’s Mike house to pick him up and take us down to the Bay, which became the center of my surfing universe. By 1968 I had graduated to a regular board after outgrowing my little belly board. When Wetteland, Durban’s largest surfboard manufacturer got into financial difficulties my Dad decided to step in and buy a portion of the business. He bought a new building for the company and with Max Wetteland entered into an agreement with 1964 World Champ Midget Farrelly to make the Farrelly boards under license. After discussions with Max and a promoter friend Ian McDonald they decided to put on the Southern hemisphere’s first professional surf contest to both promote the boards and make some money – they would bring Midget out and he would be the big draw card for the crowds and generate the media excitement as they planned to set up grandstands and charge admission and award the huge sum of 500 rand for first place. The contest was to be called the Durban 500.

Midget arrived and I was totally star struck to be in the presence of a surfing god. I watched him pull his boards out the travel bag – he’d bought 2 with him; a speed board with a narrow nose and sleek tail modeled after Hawaiian big wave boards and a double ender, a rounded egg shaped board, so called because there wasn’t much difference between the nose and the tail. There was a horrified look on Max’s face. Midget had sent along the shaping templates to Max months earlier and Max had shaped boards for all the top surfers in Durban and we all thought they were the greatest boards we had ever ridden. It turns out Max had completely misunderstood the templates. Instead of making 2 separate boards Max had made one, combining the pointy nose of the speed board with the round tail of the double ender, like a car manufacturer making a car with front of a Porsche and the rear of a Volkswagen. At the time it could have been a major design breakthrough if we’d stuck with it but Midget took one look at what had been done and the design was scrapped. I’m sure that blunder made Max cringe.

PE boy Gavin Rudolph won that first event that included a small group of vacationing Australians. Midget Farrelly put on an exhibition and really inspired all of us with his super fast surfing and fluid style. The wave of the competition had to be that of super hot Durban surfer Mike Esposito. While streaking across a North Beach wall he was dropped in on by a Hobie Cat but still managed to make the wave. The contest didn’t turn out to be the financial bonanza my Dad and his partners were counting on. By the next year my Dad had persuaded Peter Burness to take over the reins of the event and he and my Dad spent many hours plotting and planning what to do to take the contest to the next level. All the efforts were done for a simple purpose – to improve South African surfing. This was all a sideline venture for Peter who had his own successful timber business and all of his hard work along with that of my father was just a labor of love. Both of them just loved surfing and neither of them was in it for the money.

Like most white male South Africans in the apartheid era, I had to endure compulsory national service after high school graduation, and early in January 1973 I reported for duty. Through some wrangling from my Dad I was posted to Vortrekkerhoogte near Pretoria for 6 weeks of basic training and then to 83 TSD, an arsenal and tank and armored car storage facility near the Bluff, just outside of Durban. Most of the young servicemen were from Durban who had plotted to get home or were there through a lucky break. The PF’s, the Permanent Force members mostly hated us and tried to make our lives miserable. I started out sweeping an enormous storage shed with the world’s widest broom – I’d move the dust around from one side of the shed to the other, past boxes containing heavy barreled R1 rifles designed for automatic fire with beautiful wood grain stocks and mint condition Vickers machine guns from the First world War with the date stamp of 1916 clearly visible. Some of the sheds were filled with Panhards, fast reaction armored cars and other sheds contained Centurion tanks, the mainstay of the British and Israeli armored divisions. Every now and then someone would fire up a Centurion and run it around the perimeter road that ran around the base, inside the electrified fence, and barbed wire. The whole base would rattle, as the mobile earthquake would thunder around the perimeter. At each corner of the base were 4 cylindrical guard towers, about 20 feet up, reached by a metal ladder. Many a night I’d stand there standing guard with my R1 rifle and watch the world go by, dreaming of perfect waves while the Alsatian guard dogs roamed beneath me, baying like wolves looking for a kill. Sometimes I’d strategically place small stones on the steps to alert me in case the guard commander came to check up on me and curl up on the narrow concrete floor and fall asleep. Usually the stones would wake me as they fell and I’d jump to attention. One night I awoke to boots in the ribs. Sergeant Botes, the dog commander, skopping me and screaming Ek sal jou donner. Just another day in the life of a 17 year old trying to finish the army.

Having been in the military my Dad knew his way around the system and after a couple of bottles of scotch to the Sports Captain, I suddenly had a special pass to leave the base at 3pm every day to practice for the upcoming Gunston to be held at my local beach, the Bay of Plenty. The Bay Boys, a small group of local surfers had become some of the best surfers in the world under the guidance of my father who was like the Godfather of the beach. He’d stand on the wall with his binoculars never missing anyone’s wave and offering encouragement and advice to all the kids on the beach. It was a small tight crew and every session was as competitive as a contest. We all just pushed each other to the max and it helped that the Bay was one of the most consistent beach breaks in the world. We’d say – East or West Bay is Best. At low tight on the right swell you could get incredibly long right-hand tubes and at high tide there was a bowling left that peeled off perfectly into the rip current that ran out beside Patterson groin which formed the sand bar that created the break. The top surfers in no particular order were Mike Tomson, Jeremy Yeats, Kevin Todd, Mike Larmont, Bruce Jackson, Ricky Jordan and Paul Naude. There was also the young crew of Chris Cnutsen, my brother Paul Tomson, Bruce and Glen Milne, Wayne Shaw and Lista Sagnelli.

By 1973 the Gunston had become a big event and surfing had legitimate sports status. The real breakthrough had happened when Peter brought the cigarette manufacturer on board and suddenly surfing entered the big leagues. Gunston rammed surfing into the mainstream consciousness as the sport for men – men competing against each other for the ultimate wave and the ultimate prize – Gunston’s media spend and marketing dwarfed that of nearly every sporting event in the country. Lavishly produced contest short films showed in theaters across the country and surfing was everywhere across the country in billboards, magazine and newspaper ads.

In 1973 I had a dream run though the event and managed to make it through to the final, which was a closely matched affair. My biggest competition was from Wedge surfer Michael Esposito, one of the most naturally talented and explosive surfers in the world. People may have forgotten but back then the crowds on the beach for the event were huge. 30,000 people were the estimates, the largest crowd at the time for a surfing contest anywhere in the world.

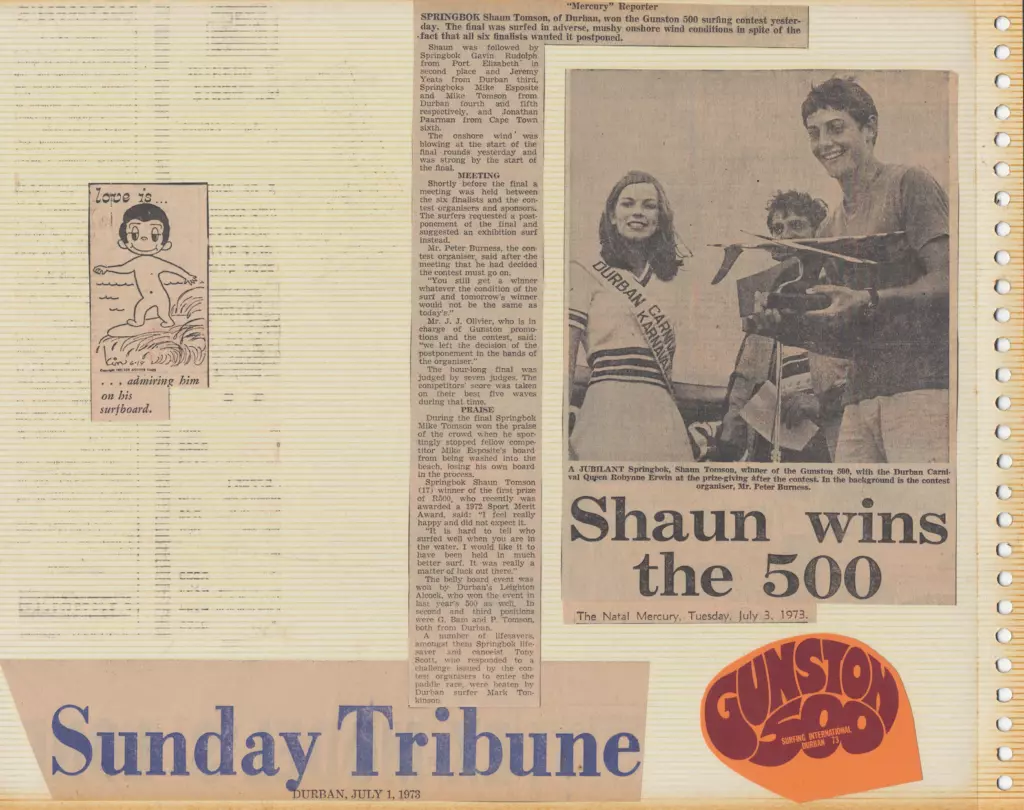

I stood on the presentation stage with the 5 other finalists in front of thousands of people. I had my short army haircut and everywhere around me was hair and more hair – this was the 70’s! I was 17 years old but looked about 13. I was a boy amongst men up on the podium, nervous as hell. My father was in the judges’ tower about 20 yards away. He was a spotter, calling the colors of the surfers as they stood up to assist the judges in their scoring. He’d stand behind the judges and I knew he could see the scores so he had a good idea of who had won. It had been a close final and I looked questioningly up at him for some form of reassurance. He shook his head and gave me the Roman Emperor’s thumbs down. I was devastated until the results were announced a couple of minutes later – I’d won! He’d known all along but he wouldn’t let a great opportunity for a practical joke to slip by. Winning was important but not that important – he put life in perspective for me.

Winning my first and sweetest Gunston 500 in 1973

As the crowd began to filter away some surfers were disappointed with the result and thought Mike Esposito should have won. One of them scrawled Tomsons go home on the showers and confronted my Dad as he was walking off the beach with my cousin Mike who had also been a finalist. Words were exchanged, things got heated and bang my father gave the guy a flathand to the head. As he turned to retaliate, bang, Mike Tomson punched him to the ground. Not a pretty episode. It was all over the papers the next day with my Dad apologizing. I’d already left the beach but I could understand my Dad’s reaction. Sport was all about honor and his honor had been questioned and he’d lost his cool.

I went on to win five more Gunstons and today, over 30 years later, they have all blended together into one event, inextricably linked with my Father who loved surfing as much as I did and who was there with me for every win. I really miss him every day. The life force glowed from him like a fire. I got a phone call while competing in Australia in 1981 that he was gone. No warning, just my mom on the other end saying how sorry she was. A son measures his own mortality by his parents. I was young, strong, and invincible, never ever contemplating death. I’d phone him after every event, often telling him I hadn’t done so good and then busting him up with the news that I’d won. I loved to play the same joke on him that he played on me at that first Gunston, the first big win of my life. He loved me to win and I loved to tell him and after he died contests were just never as fun for me again.

Hawaii 1975 – Opening for the Duke Kahanamoku Classic Contest in Hawaii

I’ve been surfing now for over 54 years; I got stoked on my first wave and that feeling has kept me going back for more ever since. I never surfed for the victories or the money or the fame, although all of it was greatly appreciated. Over the years I have helped surfers become recognized as legitimate athletes, assisted in the creation of a pro tour and participated in the growth of a multi billion-dollar surfing industry. I am proud of my involvement and contribution to the sport of surfing and I’m proud to be inextricably linked with the event my Dad started. Today it is called the Ballito Bay Pro but it is part of a tradition created by my Dad, by the best man I’ve known and it is now the longest running pro surfing contest in the world.

I still watch all the big events via the web and still take a keen interest in what is happening in the world of pro surfing. I might not know the names of all the latest hotshots and I might sometimes get confused between a slob, a mute and a lien air but I’m still excited to watch young surfers put it all on the line for a dream. When I saw South African Jordy Smith take his first big win in the Ballito Pro a few years back, under the watchful eye of his Dad Graham, I thought back to that first win of mine in the same event 4 decades years earlier watched over by my Dad too. My Dad helped make my dream come true and it was great to see history repeating itself, in the same contest, in a different era. I think a lot about my Dad today and what he did for me – helping his son make his dream come true because that’s just what Dads are supposed to do.